Making Space for Youth in Canada’s Environmental Sector

Earlier this year we hosted a learning series called “Putting Youth on the Agenda” in partnership with Youth Climate Lab’s RAD Cohort, Alliance 2030, and Community Foundations of Canada. We heard from inspiring young people about youth-led, collaborative climate action toward the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals. In the first event, Vaniartha Vaniartha and Sabrina Guzman Skotnitsky share their research on how to make making green jobs accessible for all.

We’ve all seen the job ads requiring candidates to have five years of experience for an entry-level position. When you see that, it’s discouraging. But for some, the barriers are not just experience but also residency status and access to training. As a young person, or anyone for that matter, how are you supposed to get experience without access to the job market or the training needed to enter? Young people are not a monolith, and different youth have greater barriers to employment.

In the first event in a learning series called “Putting Youth on the Agenda”, we heard from Sabrina Guzman Skotnitsky from Youth Climate Lab and Vaniartha “Vania” Vaniartha, a member of the RAD Cohort, about making green jobs more accessible for youth, with a particular focus on international students. Youth Climate Lab’s RAD Cohort program brings youth together to work on collaborative, SDG-related projects of their creation while helping youth develop the radical collaboration skills that they feel they need to be able to become leaders in the climate space.

“The Cohort,” says Vania, “aims to coordinate and promote radical collaboration among people with diverse backgrounds and create transformative actions that address the gaps to achieving climate justice.” While the Cohort put SDG 13, climate action, at the heart of their work, members of the group also brought their lived experiences to the table and developed projects and research that resonated with them while supporting other SDGs. For instance, Vania and her Cohort fellow Haruka Aoyama, also incorporated SDG 8, decent work and economic growth into their project.

“By bringing together all these unique individuals into one space, I think we’re addressing one of the challenges to radical collaboration.” Vania continues,

“We’re not creating from a singular perspective in the bubble where everyone seems to be saying, thinking, or doing the same things. We’re a diverse group of people who brought in new perspectives and fresh ideas that allowed radical collaboration to take place.”

The Cohort also uses unconventional ways of communicating climate change and climate justice, and explores how arts and storytelling can be used to communicate the issues that they’re trying to address and the possible solutions. For this group, that looks like shifting the just transition narrative to include young people, not just current fossil fuel workers, and highlighting how green jobs can address both youth un/underemployment and the climate crisis.

“Green jobs can be a lot of things,” says Sabrina, who, before her time with Youth Climate Lab completed a fellowship at the Canadian Council for Youth Prosperity. Her fellowship research focused on how to improve federally-funded green job programs to address high youth unemployment caused by COVID-19 and better support young people who face barriers to entering the environmental field. In particular, her report highlighted how international students are excluded from these programs, which is why she was keen to mentor Vania and Haruka on their project looking further into this issue.

Sabrina’s research also reveals that many people have a different definition of what a green job actually is. Google it for yourself. The definitions are varied, even contradictory, and there are plenty of them. As part of her work, Sabrina surveyed over 250 young people from across Canada, asking them to provide their own definition of a green job. The responses covered a broad range of definitions, but her preferred description defines green jobs as those that focus on the creation of a more sustainable and just future for all.

“What I love about this definition,” says Sabrina, “is it’s not necessarily talking about the tasks of the green job, but more of the role it plays in this future climate-resilient society. It’s about jobs that help us get towards that and really opens the scope of what a green job could be.”

Using that definition, already the field of green jobs grows to something far greater than the stereotypical jobs that you’d classify as a ‘green’ job. Yes, environmental scientists or hydrologists have green jobs, but politicians, community organizers, and even people doing various levels of care work can also be considered to have a green job. If we as a society are going to center SDG 13 in our lives and work, like Vania and Haruka, this definition is really important because it means any job can be a green job. Think of the possibilities! It’s not only limited to the environmental or scientific roles, but any role that benefits the environment and communities within them. So you could be a graphic designer working for an environmental organization or, like Sabrina, you could be a policy specialist.

While it’s great that we’re widening the lens of what a green job is, there are still barriers to entry, especially for youth and international students. Project Learning Tree Canada, a non-profit that administers a number of green job programs, identified three key challenges experienced by young people and students. The most common barriers youth cite are that they don’t have experience in the green field yet, they’ve never seen someone like them in a green job and haven’t met anyone who actually has a green job. They also say they don’t have the right degree, or they’re not trained in science, technology, engineering or math. Sabrina stressed the importance of Project Learning Tree Canada’s second finding, saying it speaks to representation and why that really matters. If you’ve never seen someone who looks like you doing a job that you want to do, it’s easy to imagine that perhaps it’s just not possible for you.

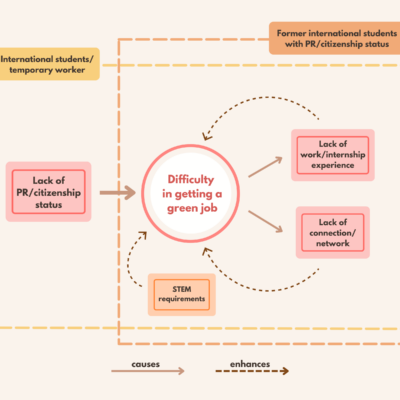

Building on Sabrina’s work, Vania and Haruka further explored the challenges faced by international students when they try to enter the green sector and ways to address these challenges. Inspired by their own experiences as international students seeking jobs in this field, they conducted a survey of 90 young people and specifically targeted current and former international students. Together, they hope their research will help raise awareness and educate policymakers on the need for policies that lower the barriers international students experience in entering the environmental workforce.

Their survey results identified four main barriers faced by participants when they tried to get a green job. These included lack of permanent resident or citizenship status, limited work or internship experience, lack of connections in the environmental field, and STEM qualifications. “The last challenges are not exclusive to international students,” says Vania, “because, as Sabrina has mentioned, this was also experienced by youth in general when they tried to enter the green sector.” It’s the first barrier listed that’s the crux of it all for international students; nearly all green job programs for students and young people require participants to be Canadian citizens, permanent residents or refugees. But something Vania and Haruka were surprised to learn is that even after students received citizenship or permanent residency, they still had difficulty getting a green job because they still lacked the experience, connections, and STEM qualifications needed. This suggests that the problems faced by international students are really twofold and systems-level and systemic problems.

First of all, international students have a higher difficulty in getting a green job as a student due to their temporary status. Because of this, they miss out on important experience and connections that would have helped them in getting a green job when they later get their permanent residency or citizenship status. Also, the emphasis on stem qualifications across the sector makes it even more difficult for those who, for example, are in the arts or social sciences to even enter the environmental field.

So what can be done to help resolve these issues and reduce barriers for young, international students to build green careers? For Vania and Haruka, the federal government should increase funding for green jobs, remove requirements on immigration status whenever possible, and legislate a just transition act to keep this work moving forward. As for employers, they don’t need to wait for the government to act. There are changes they can make today to reduce barriers by increasing employment and internship opportunities for youth and using alternate funding sources that don’t rely on an immigration status requirement.

Community members can play a role, too. They can share research like Vania, Haruka, and Sabrina’s, support campaigns and policies promoting equitable youth programs in green fields, and can share their own experiences to build awareness around this important topic. Together, everyone can act and make more green jobs accessible from coast to coast to coast.

Missed this event? Hub members can find the video recording in the portal to watch at their own pace.

The SDG Hub Learning Series and related stories are made possible with support from our partners: